DIVE DRY WITH DR. BILL #625: SARGASSUM CASCADE, PART II

Yep, I'm back this week with more thrilling tales of the trophic cascade caused by the somewhat unusual events related to our giant kelp (Macrocystis) and the nasty invasive "devil weed," Sargassum horneri (known as akamoku in Japan). You do remember last week's column where I set the stage for this week's, don't you? If not, I do understand. Too many times I go into my bedroom and forget what I was looking for. At least I have yet to forget the way to our local dive park.

To summarize, a "bottom up trophic cascade" occurs when an ecologically significant species of photosynthetic organism (plant or alga) is removed from an ecosystem. Its disappearance then affects all the "higher" trophic (feeding) levels including the plant-eaters (herbivores, or vegetarians/vegans if they are Homo sapiens) and the predators that feed on them. In this case the tasty giant kelp (Macrocystis), a food source for many of the kelp forest critters, largely disappeared from our waters due to the "perfect storm" of warm water, low nutrients and storm surge. It was replaced by the foul tasting invasive seaweed I call "devil weed" (the Sargassum)

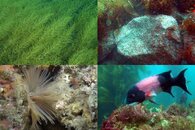

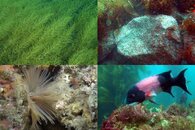

A dense carpet of Sargassum on our rocky reefs spells disaster not only for giant kelp but for all our native seaweeds. Not only does this thick growth out-compete the native species for substrate or point of attachment, it cuts out almost all sunlight reaching the rocky surface. The microscopic stages of giant kelp as well as other local algae need sunlight to grow. When it no longer can reach the rocks where they wait, they simply don't grow. In addition, the Sargassum apparently out-competes natives for nutrients since it appears to do well in low nutrient conditions.

With the help of Pete Vanags, a tech diver from San Diego, I cleared two large rocks of all the Sargassum while carefully retaining the native seaweeds. Sadly, the result was not unexpected. There was almost no native growth on the rock except for a few encrusting red alga. Sargassum had almost totally dominated the rocks, out-competing native seaweeds for sunlight and causing biodiversity to plummet. It became an almost total dominant element of the algal primary producers (photosynthesizers). But this was just its effect on the other algae in our ecosystem.

One immediately obvious effect I noticed on the herbivores or plant eaters was that our recovering abalone populations no longer had drift kelp to munch on. Since this is their primary food source, I felt it imperative to try to feed them with what little I could find. Eventually the only readily available seaweed was the devil weed (Sargassum) itself. Under more normal conditions the abalone showed a strong preference for Macrocystis and rejected Sargassum. However, as they began to starve due to the absence of giant kelp, they more readily accepted a handful of devil weed despite its reportedly nasty taste.

In Asia where the Sargassum is native, abalone and sea urchins are among its primary consumers. There these species have evolved along with the Sargassum and apparently do not find its chemical defenses (the polyphenols produced by the akamoku) entirely distasteful. Our abalone and sea urchins co-evolved with juicy giant kelp and are more accustomed to a gourmet diet of its tender blades. Heck, even I have made "Macrocystis muffins" out of flour mixed with ground up kelp blades. Yummy. Due to the warm water last summer and fall, many of our poor sea urchins died off before they faced the choice.

In looking at the density of Sargassum all through our waters, another thought struck me. In addition to cutting out the sunlight this thick growth undoubtedly limits the water circulation along the surface of the rocks. Not all kelp forest critters depend directly on giant kelp for food. A number of them such as clams, scallops, barnacle, worms and anemones are filter or suspension feeders relying on the currents to bring plankton and tasty organic tidbits to them. Without adequate water flow along the rocks they attach to, their food supply is likewise limited by the presence of "devil weed."

There may be an off-setting factor involved with the Sargassum and its effects on encrusting filter and suspension feeders. The dense growth also hides them from the prying eyes of certain predators like male sheephead that often prowl the rocky reef. Therefore the predators are also affected in terms of trophic functioning (finding food) due to the invasive seaweed. This is not directly a part of the trophic (feeding) cascade but it affects the food webs. The poor boys will have to go out over the sandy bottom and dig for their supper like their ladies do. I've even observed lazy males watch as the girls do the initial digging, and then swoop in chase away the female and continue the search for buried "treasure."

Giant kelp is not just a food source for other critters. It also provides protection from predators for a host of animals. Filter feeding species like blacksmith, jack mackerel and topsmelt often use its cover to hide from barracuda, yellowtail and kelp bass. The absence of giant kelp forest makes hiding rather difficult for these mid-water species. They can continue chowing down on plankton-based foods but risk getting munched themselves. I've noticed yellowtail still in the dive park in early February. Now I'm wondering if it is the warmer than usual water temperatures that keep them here, or the easier pickings of their prey?

Although I'm a scientist by training, my analysis of these Sargassum-related impacts is derived from anecdotal observations. As such, they are really nothing more than hypotheses or theories about what is happening. Many of my academic peers would justly call them that and would require months of monitoring and other scientific methods to produce results that could be used to substantiate this and influence our policy makers in Sacramento. Since I'm pretty much retired these days, I'll leave that for them. This is something our state Department of Fish & Wildlife or university grad students and faculty should be doing. After all, they get paid for it. I'm just a fun-loving dive bum living on Social Security with little time or money for such endeavors these days!

© 2015 Dr. Bill Bushing. For the entire archived set of over 600 "Dive Dry" columns, visit my website Star Thrower Educational Multimedia (S.T.E.M.) Home Page

Image caption: Dense Sargassum monoculture blocking out sunlight and nearly barren rock after Sargassum removed; suspension feeding tube worm and male sheephead searching for food over reef before Sargassum invasion.

Yep, I'm back this week with more thrilling tales of the trophic cascade caused by the somewhat unusual events related to our giant kelp (Macrocystis) and the nasty invasive "devil weed," Sargassum horneri (known as akamoku in Japan). You do remember last week's column where I set the stage for this week's, don't you? If not, I do understand. Too many times I go into my bedroom and forget what I was looking for. At least I have yet to forget the way to our local dive park.

To summarize, a "bottom up trophic cascade" occurs when an ecologically significant species of photosynthetic organism (plant or alga) is removed from an ecosystem. Its disappearance then affects all the "higher" trophic (feeding) levels including the plant-eaters (herbivores, or vegetarians/vegans if they are Homo sapiens) and the predators that feed on them. In this case the tasty giant kelp (Macrocystis), a food source for many of the kelp forest critters, largely disappeared from our waters due to the "perfect storm" of warm water, low nutrients and storm surge. It was replaced by the foul tasting invasive seaweed I call "devil weed" (the Sargassum)

A dense carpet of Sargassum on our rocky reefs spells disaster not only for giant kelp but for all our native seaweeds. Not only does this thick growth out-compete the native species for substrate or point of attachment, it cuts out almost all sunlight reaching the rocky surface. The microscopic stages of giant kelp as well as other local algae need sunlight to grow. When it no longer can reach the rocks where they wait, they simply don't grow. In addition, the Sargassum apparently out-competes natives for nutrients since it appears to do well in low nutrient conditions.

With the help of Pete Vanags, a tech diver from San Diego, I cleared two large rocks of all the Sargassum while carefully retaining the native seaweeds. Sadly, the result was not unexpected. There was almost no native growth on the rock except for a few encrusting red alga. Sargassum had almost totally dominated the rocks, out-competing native seaweeds for sunlight and causing biodiversity to plummet. It became an almost total dominant element of the algal primary producers (photosynthesizers). But this was just its effect on the other algae in our ecosystem.

One immediately obvious effect I noticed on the herbivores or plant eaters was that our recovering abalone populations no longer had drift kelp to munch on. Since this is their primary food source, I felt it imperative to try to feed them with what little I could find. Eventually the only readily available seaweed was the devil weed (Sargassum) itself. Under more normal conditions the abalone showed a strong preference for Macrocystis and rejected Sargassum. However, as they began to starve due to the absence of giant kelp, they more readily accepted a handful of devil weed despite its reportedly nasty taste.

In Asia where the Sargassum is native, abalone and sea urchins are among its primary consumers. There these species have evolved along with the Sargassum and apparently do not find its chemical defenses (the polyphenols produced by the akamoku) entirely distasteful. Our abalone and sea urchins co-evolved with juicy giant kelp and are more accustomed to a gourmet diet of its tender blades. Heck, even I have made "Macrocystis muffins" out of flour mixed with ground up kelp blades. Yummy. Due to the warm water last summer and fall, many of our poor sea urchins died off before they faced the choice.

In looking at the density of Sargassum all through our waters, another thought struck me. In addition to cutting out the sunlight this thick growth undoubtedly limits the water circulation along the surface of the rocks. Not all kelp forest critters depend directly on giant kelp for food. A number of them such as clams, scallops, barnacle, worms and anemones are filter or suspension feeders relying on the currents to bring plankton and tasty organic tidbits to them. Without adequate water flow along the rocks they attach to, their food supply is likewise limited by the presence of "devil weed."

There may be an off-setting factor involved with the Sargassum and its effects on encrusting filter and suspension feeders. The dense growth also hides them from the prying eyes of certain predators like male sheephead that often prowl the rocky reef. Therefore the predators are also affected in terms of trophic functioning (finding food) due to the invasive seaweed. This is not directly a part of the trophic (feeding) cascade but it affects the food webs. The poor boys will have to go out over the sandy bottom and dig for their supper like their ladies do. I've even observed lazy males watch as the girls do the initial digging, and then swoop in chase away the female and continue the search for buried "treasure."

Giant kelp is not just a food source for other critters. It also provides protection from predators for a host of animals. Filter feeding species like blacksmith, jack mackerel and topsmelt often use its cover to hide from barracuda, yellowtail and kelp bass. The absence of giant kelp forest makes hiding rather difficult for these mid-water species. They can continue chowing down on plankton-based foods but risk getting munched themselves. I've noticed yellowtail still in the dive park in early February. Now I'm wondering if it is the warmer than usual water temperatures that keep them here, or the easier pickings of their prey?

Although I'm a scientist by training, my analysis of these Sargassum-related impacts is derived from anecdotal observations. As such, they are really nothing more than hypotheses or theories about what is happening. Many of my academic peers would justly call them that and would require months of monitoring and other scientific methods to produce results that could be used to substantiate this and influence our policy makers in Sacramento. Since I'm pretty much retired these days, I'll leave that for them. This is something our state Department of Fish & Wildlife or university grad students and faculty should be doing. After all, they get paid for it. I'm just a fun-loving dive bum living on Social Security with little time or money for such endeavors these days!

© 2015 Dr. Bill Bushing. For the entire archived set of over 600 "Dive Dry" columns, visit my website Star Thrower Educational Multimedia (S.T.E.M.) Home Page

Image caption: Dense Sargassum monoculture blocking out sunlight and nearly barren rock after Sargassum removed; suspension feeding tube worm and male sheephead searching for food over reef before Sargassum invasion.