Hi All:

Back in July, I posted a thread about quarry diving and the attraction that "Scuba Parks" had to east coast divers. I appreciate many of the thoughtful replies to that thread and the discussion it generated. Great stuff. In that thread, I said this:

So, today, I'm going to try and show you "what I've seen." On the afternoon of August 5th, I left DC hoping the weather off Cape Hatteras would cooperate and the remains of TS Emily wouldn't spoil the weekend. By Friday night, it was still looking iffy, with rougher weather moving north from the south. I got to Virginia Beach, loaded my gear, slept a few hours, and left for Hatteras at 3 AM. Three hours later I was at the dock of the Under Pressure in Hatteras Village, getting ready to go. My fellow divers, Kristine, Mike, Chip, Scott and Bobby were already loaded. Captain JT Barker talked to fishing boats that left the inlet earlier, getting reports that the Gulf Stream seemed cooperative. About three hours later, on Saturday, August 6th, we arrived at the coordinates for the E.M. Clark and knew we had good conditions for what turned out to be an epic ocean dive.

The E.M. Clark was a 500 FT long 10,000 ton tanker torpedoed by the German Submarine U-124 in March, 1942. The ship sank fast, killing one of the crew, probably as a result of the torpedo explosion. All others escaped in a lifeboat. The Clark sank in almost a perfect location, deep enough so as not to be a hazard to ship navigation, but at a spot where the force of the Gulf Stream probably turned the ship as she sank, ending up on her port side in 240 FT of water. Because the Clark is 60 FT wide, she now towers above the ocean bottom, more than five stories above the sand. Unlike other wrecks, she was never depth charged or wire dragged, so except for the forces of nature, the E.M. Clark lays completely intact, resting quietly for almost 60 years.

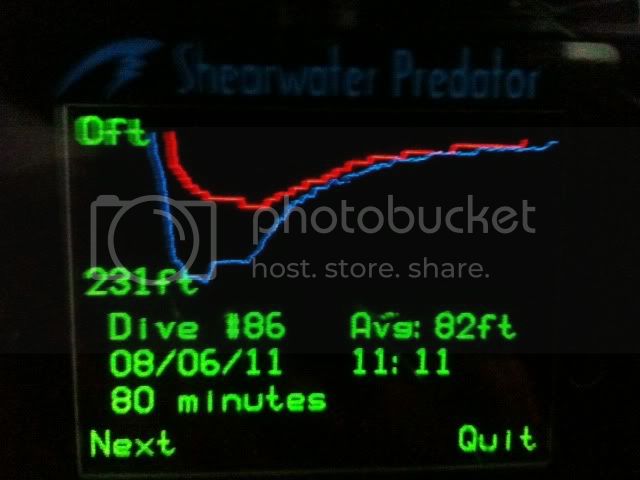

Because of the depth, we can't use air or Nitrox to make the dive. Instead, we use a mixture of 17% Oxygen and 50% Helium (17/50), called Trimix, to breath at depth. To decompress, we switch to 50% Oxygen (50/50) at 70 FT, then 75% Oxygen at 30 FT. Using these gas mixtures, we dive a planned bottom time of 20 min, followed by a decompression time of 60 min. This allows open circuit divers to wear doubles with the 17/50 mix, and a 40 CFT "pony bottle" (we call them "stage bottles") slung under each arm for decompression. "Run time," or our total time underwater, was planned for 80 minutes. Without the Oxygen mixes, decompression time would extend to 3 HRS, increasing run time to more than 200 minutes. The picture below is my dive computer's graph of the dive. The blue line is depth and time. The red line is our decompression "ceiling." Our first decompression stop was at 150 FT.

Kristine, my dive buddy and I, were the last to splash. Scott, a rebreather diver, went first, followed by Chip and then Mike, our photographer. After a quick safety check at 30 FT, Kristine and I descended to the hull at 190 FT. Unfortunately, the E.M. Clark is notorious for strong currents and difficult conditions. Everyone on the boat, except for me, had never seen "perfect" conditions on the Clark, even after 5 years of diving her.

Today, however, was the day. We arrived at the top of the hull and, looking up, could see the dive boat sitting motionless on the surface. The Gulf Stream water was a warm 82 degrees, but had dropped to the low 70s at the wreck. The length of the wreck stretched to our left and right, with more than 100 FT of visibility in each direction.

I often tell other divers that calling the E.M. Clark "just a shipwreck" is like calling Notre Dame "just a church." Until you see it and can experience it, there's just no comparison. Thousands of fish exploded in every direction from the wreck as we swam. Large, 50+ LB Amberjacks were everywhere. Sand Tiger Sharks hovered in and out of the wreckage.

I knew Kristine wanted to see the huge prop at the stern, so we turned left and dropped to 230 FT, the wreck looming over us. Swimming with a mild current, we rounded the stern only 7 minutes into our dive. As we crossed the stern and ascended, I saw the prop. At the same time, I heard Kristine begin to yell through her regulator at the sight. She had tried to reach this point several times before, but could never make it.

As she crossed the prop, the sheer size of the blades dwarfed her. The prop projects upward and out from the wreck, defying the forces of both sea and gravity for almost 60 years. The rudder is even larger, deflected downward toward the sand. We circled the area for a few minutes, awed by what we saw. The grin on my face was so wide, I didn't need teeth to hold my regulator.

Reaching the end of our loop, we began the swim back to the anchor line. Staying on the top of the hull and looking down, we had a birds eye view of the sea bottom from the top of the wreck. We passed the very same davits, now empty, that the crew of the Clark used to launch their lifeboat back in 1942.

Time stood still as we reached the anchor and met up with the other divers coming back from the bow. At exactly 20 min, we left the bottom and began the long climb through one hour of decompression above us. All of us met up at 20 FT, finishing the long stretch on Oxygen to offload our excess Nitrogen before surfacing.

Most of the photos you've seen in this post were taken by Mike Boring, one heck of a good photographer (even though he doesn't like people to know it). His work has been seen in Wreck Diver Magazine and other publications. The stern and prop, along with the bow photo, were taken by the NOAA Shipwreck Project, a government funded project to document and survey WWII wrecks off the east coast. They visited the wreck just a few days after us.

I've posted this thread to Basic Scuba Discussions because I think we focus sometimes too much on stuff that doesn't help new divers understand what's really important about diving. It isn't about having "perfect" skills or wearing doubles or getting that "just right" "L shape" position for your profile picture to show everyone how good you look, LOL. Nope, it's not about any of that. Instead, it's about diving. It's about the awe you will feel that few others do. It's about the feeling of flying underwater, experiencing the unique history of our country while encountering the wide variety of marine life you can only see in the ocean. None of that other stuff matters at all when you're out here.

So, if you really want to experience diving and see what some of us get to see, I have one simple recommendation.

Get out here. JOIN us!

Thanks for reading...

Andy

Back in July, I posted a thread about quarry diving and the attraction that "Scuba Parks" had to east coast divers. I appreciate many of the thoughtful replies to that thread and the discussion it generated. Great stuff. In that thread, I said this:

BUT, I wish you could see what I've seen. Molasses Reef in Key Largo on a dark night bathed in the blue light of photogenic plankton so bright that you didn't even need a dive light. Thousands of horseshoe crabs migrating across the sandy bottom of the entrance to the Chesapeake Bay like soldiers marching into battle. The look on my 13 year old niece's face as we lay motionless near the stern of the Dixie Arrow off Hatteras after other divers had left the wreck and more than 20 sand tiger sharks moved in right next to us, some more than 10 FT long, floating effortlessly only inches away. The shear size of the WWII tanker E.M. Clark lying on its side and towering more than 6 stories above me in almost unlimited visibility as we casually swam down the length of her hull. The U.S.S. Tarpon bathed in blue topaz water so beautiful that it sparkled like jewelry when baitfish caught the beams of sunlight. A pod of spotted dolphin smiling as they swam by and made my acquaintance on a decompression stop.

So, today, I'm going to try and show you "what I've seen." On the afternoon of August 5th, I left DC hoping the weather off Cape Hatteras would cooperate and the remains of TS Emily wouldn't spoil the weekend. By Friday night, it was still looking iffy, with rougher weather moving north from the south. I got to Virginia Beach, loaded my gear, slept a few hours, and left for Hatteras at 3 AM. Three hours later I was at the dock of the Under Pressure in Hatteras Village, getting ready to go. My fellow divers, Kristine, Mike, Chip, Scott and Bobby were already loaded. Captain JT Barker talked to fishing boats that left the inlet earlier, getting reports that the Gulf Stream seemed cooperative. About three hours later, on Saturday, August 6th, we arrived at the coordinates for the E.M. Clark and knew we had good conditions for what turned out to be an epic ocean dive.

The E.M. Clark was a 500 FT long 10,000 ton tanker torpedoed by the German Submarine U-124 in March, 1942. The ship sank fast, killing one of the crew, probably as a result of the torpedo explosion. All others escaped in a lifeboat. The Clark sank in almost a perfect location, deep enough so as not to be a hazard to ship navigation, but at a spot where the force of the Gulf Stream probably turned the ship as she sank, ending up on her port side in 240 FT of water. Because the Clark is 60 FT wide, she now towers above the ocean bottom, more than five stories above the sand. Unlike other wrecks, she was never depth charged or wire dragged, so except for the forces of nature, the E.M. Clark lays completely intact, resting quietly for almost 60 years.

Because of the depth, we can't use air or Nitrox to make the dive. Instead, we use a mixture of 17% Oxygen and 50% Helium (17/50), called Trimix, to breath at depth. To decompress, we switch to 50% Oxygen (50/50) at 70 FT, then 75% Oxygen at 30 FT. Using these gas mixtures, we dive a planned bottom time of 20 min, followed by a decompression time of 60 min. This allows open circuit divers to wear doubles with the 17/50 mix, and a 40 CFT "pony bottle" (we call them "stage bottles") slung under each arm for decompression. "Run time," or our total time underwater, was planned for 80 minutes. Without the Oxygen mixes, decompression time would extend to 3 HRS, increasing run time to more than 200 minutes. The picture below is my dive computer's graph of the dive. The blue line is depth and time. The red line is our decompression "ceiling." Our first decompression stop was at 150 FT.

Kristine, my dive buddy and I, were the last to splash. Scott, a rebreather diver, went first, followed by Chip and then Mike, our photographer. After a quick safety check at 30 FT, Kristine and I descended to the hull at 190 FT. Unfortunately, the E.M. Clark is notorious for strong currents and difficult conditions. Everyone on the boat, except for me, had never seen "perfect" conditions on the Clark, even after 5 years of diving her.

Today, however, was the day. We arrived at the top of the hull and, looking up, could see the dive boat sitting motionless on the surface. The Gulf Stream water was a warm 82 degrees, but had dropped to the low 70s at the wreck. The length of the wreck stretched to our left and right, with more than 100 FT of visibility in each direction.

I often tell other divers that calling the E.M. Clark "just a shipwreck" is like calling Notre Dame "just a church." Until you see it and can experience it, there's just no comparison. Thousands of fish exploded in every direction from the wreck as we swam. Large, 50+ LB Amberjacks were everywhere. Sand Tiger Sharks hovered in and out of the wreckage.

I knew Kristine wanted to see the huge prop at the stern, so we turned left and dropped to 230 FT, the wreck looming over us. Swimming with a mild current, we rounded the stern only 7 minutes into our dive. As we crossed the stern and ascended, I saw the prop. At the same time, I heard Kristine begin to yell through her regulator at the sight. She had tried to reach this point several times before, but could never make it.

As she crossed the prop, the sheer size of the blades dwarfed her. The prop projects upward and out from the wreck, defying the forces of both sea and gravity for almost 60 years. The rudder is even larger, deflected downward toward the sand. We circled the area for a few minutes, awed by what we saw. The grin on my face was so wide, I didn't need teeth to hold my regulator.

Reaching the end of our loop, we began the swim back to the anchor line. Staying on the top of the hull and looking down, we had a birds eye view of the sea bottom from the top of the wreck. We passed the very same davits, now empty, that the crew of the Clark used to launch their lifeboat back in 1942.

Time stood still as we reached the anchor and met up with the other divers coming back from the bow. At exactly 20 min, we left the bottom and began the long climb through one hour of decompression above us. All of us met up at 20 FT, finishing the long stretch on Oxygen to offload our excess Nitrogen before surfacing.

Most of the photos you've seen in this post were taken by Mike Boring, one heck of a good photographer (even though he doesn't like people to know it). His work has been seen in Wreck Diver Magazine and other publications. The stern and prop, along with the bow photo, were taken by the NOAA Shipwreck Project, a government funded project to document and survey WWII wrecks off the east coast. They visited the wreck just a few days after us.

I've posted this thread to Basic Scuba Discussions because I think we focus sometimes too much on stuff that doesn't help new divers understand what's really important about diving. It isn't about having "perfect" skills or wearing doubles or getting that "just right" "L shape" position for your profile picture to show everyone how good you look, LOL. Nope, it's not about any of that. Instead, it's about diving. It's about the awe you will feel that few others do. It's about the feeling of flying underwater, experiencing the unique history of our country while encountering the wide variety of marine life you can only see in the ocean. None of that other stuff matters at all when you're out here.

So, if you really want to experience diving and see what some of us get to see, I have one simple recommendation.

Get out here. JOIN us!

Thanks for reading...

Andy