Gareth

GUE Instructor

In the past I have written extensively about buoyancy control, but on re-reading those articles it appears that the focus was on the macro elements of buoyancy control and not the micro. It is the micro changes that make real savings in terms of gas usage and efficiency, so I thought I would put some ideas down on fine tuning buoyancy control. This will hopefully be of interest to anyone interested in mastering buoyancy control.

Lets start with a generalisation. Everyone dives negatively buoyant.

OK, now in fairness, obviously the above is not true. Obviously there are plenty of people who dive neutrally buoyant. Its just I dont ever get to meet them. The people that come to me invariably have buoyancy control issues, and invariably they are negatively buoyant.

Firstly, how do I know this is the case. How do I know that someone is negatively buoyant. Put them on a platform and they appear to be hovering over it without moving up or down. Are they neutrally buoyant? Not necessarily by what is admittedly my own definition. Look at the following image

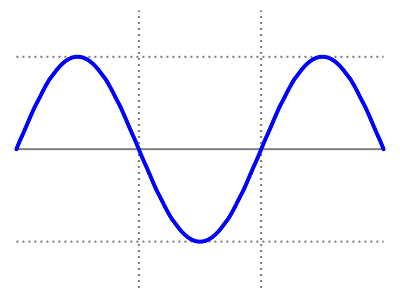

Think about this image as your breathing pattern. At the top is a completed inhalation. At the bottom is a completed exhalation. Its nice and regular, isnt it. Nice, slow, full breathing. This will ensure your lungs are working at maximum efficiency, and minimise Carbon Dioxide buildup. Well done you.

So where does Buoyancy control come in?

My definition of neutrally buoyant is this;

a diver that it totally stationary in the water column when they are half way through their breathing pattern. They will ascend if they take a full breathe in and hold it. They will descend if they completely exhale, and hold it.

And here in lies the problem.

A considerable number of divers do not know this, and thus do not strive for it. Take a typical situation of a diver descending down a shotline. As they approach the bottom, they see a wreck emerge out of the gloom. Its becoming unfashionable to just slam into it, so they try to avoid doing so. They inject a huge amount of gas into their BCD. However, our UK waters are not condusive to adequate preparation, and we often do not have enough time to inject an appropriate amount of gas. Equally, people are afraid of putting too much gas in their BCD. So what do they do?

To stop them from hitting the wreck they take a massive lungful of gas and hold it in. They then hover motionless above the wreck. They are, I repeat, not neutrally buoyant at this point.

This is also demonstrated nicely by some new CCR divers, who have often developed this habit whilst diving OC, and nose dive into the bottom the first few times they descend because of course the gas volume, and thus the buoyancy is not changing with their breathing.

Nothing wrong with this in OC diving, as long as the next thing that happens is an adjustment. They need to adjust their buoyancy devices so that they are once again neutrally buoyant in the middle of their breathing pattern. Unfortunately, this is rarely done for a couple of reasons. Firstly, people are fairly task loaded at this point. They have the wreck in front of them, they have to get their bearings, find their buddy, get swimming etc. They are distracted by looking at things.

What happens is they end up breathing in the top half of their breathing pattern, the top half of their lungs. This is a very inefficient way to breathe. The brain is quite remarkable in that it puts a mental filter in place, and people just breathe consciously in the top half of their lungs. It takes very little capacity to do this.

It does, however, take some capacity.

When that person forgets to breathe in this manner, they breathe out past the half way point and obviously become negatively buoyant. This can be seen in people who every now and again place a hand, or even just a finger, against the wreck. They havent suddenly been pushed down. They are just very slightly negatively buoyant. Watch for it in yourself and other divers, you might be surprised. With some divers it might be an aggressive hand placed on the wreck to push them back up. With others it might just be a finger tapping against it every minute or so as they drift down. The underlying problem is the same in both cases.

You also see this in divers who appear to be neutrally buoyant, but immediately descend once they are given something else to do, such as put up an SMB. All that has happened is that they no longer have the spare capacity to remember to breathe in a specific way. Their autonomous systems take over the job of breathing, they breathe out, and down they go.

The example I gave above of an initial descent followed by a failure to adjust properly is just part of the issue. The same occurs when a diver is required to change depth during the dive when, for example, swimming over part of a wreck. They make an adjustment with their BCD or wing which takes care of the macro change, but they do not finely adjust it. They then unconsciously remain neutrally buoyant by adjusting their breathing.

There is also a mental game I see in a lot of diving. It is very comforting to many divers to remain slightly negatively buoyant. At the top of their breathing pattern they are perfectly neutral, and at the bottom they are slightly negative, which means they are not going to rocket to the surface. Many people find this very comforting. This is demonstrated nicely by forcing people to become neutrally buoyant, and they usually report a feeling of lightness or a worry that they were actually drifting up to the surface. This is very common on fundamentals, and it is usually only the video that proves to people that they were actually just hovering in place rather than rising uncontrollably to the surface.

It is far less frequent, but the opposite is also true some divers keep themselves slightly positively buoyant. As I said, this is far more rare, but I have seen it. In this scenario a diver will have typically ascended part of the way up a wreck, and will then swim along at the same depth by breathing in the lower half of their lungs. Again, once they are distracted by something and conscious control of their breathing pattern is lost, they usually end up rising and having to make a macro adjustment with their BCD or wing.

Without reiterating all the other articles that I have written, and remembering the caveat at the beginning of this article that this might only be of interest to people who want to master buoyancy control, lets just assume for the sake of politeness that this is a problem and we want to resolve it. In a nutshell, it means that people are having to focus on their breathing rather than the dive, and they risk losing control if they become task loaded. They will also be disturbing whatever it is they are swimming over, and will be using more gas than they need to.

So how do we fix the problem?

Well, the first thing we have to do is to get over a historic evil. The lesson never hold your breath when scuba diving. This is, of course, a necessary evil for brand new scuba divers, but is a nonsense for experienced divers. the rule is embedded in the materials of training agencies, and is often called the first or golden rule. From a psychological perspective this rule is a nonsense. Firstly, holding your breathe when neutrally buoyant or descending should not be an issue. Secondly, it reinforces a negative, which educational psychologists have known for decades is a really bad idea.Never hold your breathe, never hold your breathe, hold your breathe, hold your breathe .

A far more sensible rule would be always breathe normally when ascending.

Lets assume we are going to hold our breathe now and again. Dont worry, I wont tell. This gives us the ability to run a little buoyancy test. Relax, and take a few normal breaths. Ensure you are breathing normally you might actually have to consciously do this. Now, after a few nice slow breaths just let about half the gas out of your lungs and, wait for it, stop breathing. Stop. You need to be fairly ruthless with yourself to let half the gas out. Your instinct will be to let less than half out, which of course helps the issue but does not solve it. Try it again. this time make sure you are not waggling your arms or legs to compensate. Keep still. Freeze, in fact. Once youve got an idea of where half way out is take a look at what happens to you when you stop breathing. Do you go up. Bet you dont. Do you go down? Thought so.

Lets call this a micro buoyancy check. I run this check at the bottom of the shotline, and whenever I change depth during the dive. On the way up, I do it when I come to decompression stops.

Being neutrally buoyant in this manner causes the stress levels to drop quite dramatically, especially at decompression stops where you might have gas switches etc to perform. It means you can initiate descents by simply breathing out and holding it for a second. You can initiate ascents by simply breathing in although here you really do need to be careful to only hold it until you start moving.

so next time you are floating motionless and think you are perfectly neutrally buoyant, just take a moment and see if you really are.

Anyway, dive safe.

Garf

Lets start with a generalisation. Everyone dives negatively buoyant.

OK, now in fairness, obviously the above is not true. Obviously there are plenty of people who dive neutrally buoyant. Its just I dont ever get to meet them. The people that come to me invariably have buoyancy control issues, and invariably they are negatively buoyant.

Firstly, how do I know this is the case. How do I know that someone is negatively buoyant. Put them on a platform and they appear to be hovering over it without moving up or down. Are they neutrally buoyant? Not necessarily by what is admittedly my own definition. Look at the following image

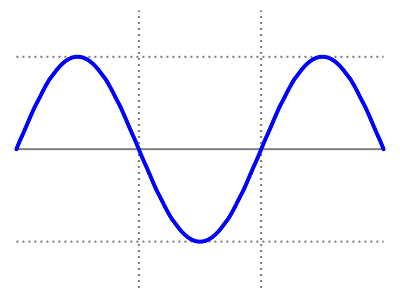

Think about this image as your breathing pattern. At the top is a completed inhalation. At the bottom is a completed exhalation. Its nice and regular, isnt it. Nice, slow, full breathing. This will ensure your lungs are working at maximum efficiency, and minimise Carbon Dioxide buildup. Well done you.

So where does Buoyancy control come in?

My definition of neutrally buoyant is this;

a diver that it totally stationary in the water column when they are half way through their breathing pattern. They will ascend if they take a full breathe in and hold it. They will descend if they completely exhale, and hold it.

And here in lies the problem.

A considerable number of divers do not know this, and thus do not strive for it. Take a typical situation of a diver descending down a shotline. As they approach the bottom, they see a wreck emerge out of the gloom. Its becoming unfashionable to just slam into it, so they try to avoid doing so. They inject a huge amount of gas into their BCD. However, our UK waters are not condusive to adequate preparation, and we often do not have enough time to inject an appropriate amount of gas. Equally, people are afraid of putting too much gas in their BCD. So what do they do?

To stop them from hitting the wreck they take a massive lungful of gas and hold it in. They then hover motionless above the wreck. They are, I repeat, not neutrally buoyant at this point.

This is also demonstrated nicely by some new CCR divers, who have often developed this habit whilst diving OC, and nose dive into the bottom the first few times they descend because of course the gas volume, and thus the buoyancy is not changing with their breathing.

Nothing wrong with this in OC diving, as long as the next thing that happens is an adjustment. They need to adjust their buoyancy devices so that they are once again neutrally buoyant in the middle of their breathing pattern. Unfortunately, this is rarely done for a couple of reasons. Firstly, people are fairly task loaded at this point. They have the wreck in front of them, they have to get their bearings, find their buddy, get swimming etc. They are distracted by looking at things.

What happens is they end up breathing in the top half of their breathing pattern, the top half of their lungs. This is a very inefficient way to breathe. The brain is quite remarkable in that it puts a mental filter in place, and people just breathe consciously in the top half of their lungs. It takes very little capacity to do this.

It does, however, take some capacity.

When that person forgets to breathe in this manner, they breathe out past the half way point and obviously become negatively buoyant. This can be seen in people who every now and again place a hand, or even just a finger, against the wreck. They havent suddenly been pushed down. They are just very slightly negatively buoyant. Watch for it in yourself and other divers, you might be surprised. With some divers it might be an aggressive hand placed on the wreck to push them back up. With others it might just be a finger tapping against it every minute or so as they drift down. The underlying problem is the same in both cases.

You also see this in divers who appear to be neutrally buoyant, but immediately descend once they are given something else to do, such as put up an SMB. All that has happened is that they no longer have the spare capacity to remember to breathe in a specific way. Their autonomous systems take over the job of breathing, they breathe out, and down they go.

The example I gave above of an initial descent followed by a failure to adjust properly is just part of the issue. The same occurs when a diver is required to change depth during the dive when, for example, swimming over part of a wreck. They make an adjustment with their BCD or wing which takes care of the macro change, but they do not finely adjust it. They then unconsciously remain neutrally buoyant by adjusting their breathing.

There is also a mental game I see in a lot of diving. It is very comforting to many divers to remain slightly negatively buoyant. At the top of their breathing pattern they are perfectly neutral, and at the bottom they are slightly negative, which means they are not going to rocket to the surface. Many people find this very comforting. This is demonstrated nicely by forcing people to become neutrally buoyant, and they usually report a feeling of lightness or a worry that they were actually drifting up to the surface. This is very common on fundamentals, and it is usually only the video that proves to people that they were actually just hovering in place rather than rising uncontrollably to the surface.

It is far less frequent, but the opposite is also true some divers keep themselves slightly positively buoyant. As I said, this is far more rare, but I have seen it. In this scenario a diver will have typically ascended part of the way up a wreck, and will then swim along at the same depth by breathing in the lower half of their lungs. Again, once they are distracted by something and conscious control of their breathing pattern is lost, they usually end up rising and having to make a macro adjustment with their BCD or wing.

Without reiterating all the other articles that I have written, and remembering the caveat at the beginning of this article that this might only be of interest to people who want to master buoyancy control, lets just assume for the sake of politeness that this is a problem and we want to resolve it. In a nutshell, it means that people are having to focus on their breathing rather than the dive, and they risk losing control if they become task loaded. They will also be disturbing whatever it is they are swimming over, and will be using more gas than they need to.

So how do we fix the problem?

Well, the first thing we have to do is to get over a historic evil. The lesson never hold your breath when scuba diving. This is, of course, a necessary evil for brand new scuba divers, but is a nonsense for experienced divers. the rule is embedded in the materials of training agencies, and is often called the first or golden rule. From a psychological perspective this rule is a nonsense. Firstly, holding your breathe when neutrally buoyant or descending should not be an issue. Secondly, it reinforces a negative, which educational psychologists have known for decades is a really bad idea.Never hold your breathe, never hold your breathe, hold your breathe, hold your breathe .

A far more sensible rule would be always breathe normally when ascending.

Lets assume we are going to hold our breathe now and again. Dont worry, I wont tell. This gives us the ability to run a little buoyancy test. Relax, and take a few normal breaths. Ensure you are breathing normally you might actually have to consciously do this. Now, after a few nice slow breaths just let about half the gas out of your lungs and, wait for it, stop breathing. Stop. You need to be fairly ruthless with yourself to let half the gas out. Your instinct will be to let less than half out, which of course helps the issue but does not solve it. Try it again. this time make sure you are not waggling your arms or legs to compensate. Keep still. Freeze, in fact. Once youve got an idea of where half way out is take a look at what happens to you when you stop breathing. Do you go up. Bet you dont. Do you go down? Thought so.

Lets call this a micro buoyancy check. I run this check at the bottom of the shotline, and whenever I change depth during the dive. On the way up, I do it when I come to decompression stops.

Being neutrally buoyant in this manner causes the stress levels to drop quite dramatically, especially at decompression stops where you might have gas switches etc to perform. It means you can initiate descents by simply breathing out and holding it for a second. You can initiate ascents by simply breathing in although here you really do need to be careful to only hold it until you start moving.

so next time you are floating motionless and think you are perfectly neutrally buoyant, just take a moment and see if you really are.

Anyway, dive safe.

Garf