Well...if the thread was not off topic before it really is now...

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Rock Bottom/Turn Pressure/Rule of xths for Doubles?

- Thread starter Reg Braithwaite

- Start date

Please register or login

Welcome to ScubaBoard, the world's largest scuba diving community. Registration is not required to read the forums, but we encourage you to join. Joining has its benefits and enables you to participate in the discussions.

Benefits of registering include

- Ability to post and comment on topics and discussions.

- A Free photo gallery to share your dive photos with the world.

- You can make this box go away

Reg Braithwaite

Contributor

like this thread btw

What I was trying to say was that there is a technically interesting thread about what is an appropriate level of commitment/appropriate level of risk mitigation/appropriate strategy for gas planning with isolated doubles AND there is a culturally interesting thread about what people consider "recreational" and "technical" diving.

Although one led to the other, I wondered if the latter doesn't deserve its own thread with its own subject line so that others can find it more easily.

Surelyshirly

Contributor

- Messages

- 519

- Reaction score

- 8

- # of dives

- 200 - 499

as per the OP...... I see no one has addressed the fact that..... in a recreational dive, you would not be doing an overhead dive such as a cave..... and you would not be using AL 80's for a cave, or double 40's...... anyway, for an average non overhead dive, your rule of thirds can cover multiple failures as your route to the surface does not have to be as long as your route to where ever you are was. Swim along for 40 minutes, have a multiple failures and swim to the surface, not back to your original starting point. This generally uses less gas than you planned on having even in an emergency.

at least my opinion thereof

at least my opinion thereof

Reg Braithwaite

Contributor

for an average non overhead dive, your rule of thirds can cover multiple failures as your route to the surface does not have to be as long as your route to where ever you are was. Swim along for 40 minutes, have a multiple failures and swim to the surface, not back to your original starting point. This generally uses less gas than you planned on having even in an emergency.

Some people use gas management strategies like Rock Bottom that take this into account. For example, if we plan to drop onto a reef at 70', swim along it for a certain time, rise to the top of the reef at 40' and swim back to the starting point along the top of the reef, then ascend to the boat, we really don't need to take returning to the boat into account when planning for an emergency, just as you say.

We start with two values: Rock Bottom for 70' and Rock Bottom for 40', each of which represents enough gas such that if one diver go OOG, we can spend a minute getting things under control, then (in this case) making a safe ascent directly to the surface.

We then need a third value, our turn point, which represents enough gas to turn the dive at 70' and make it home with a small safety margin (representing the inaccuracy of our gauge and taking some small variability of consumption unto account).

Thus armed, we descend to 70' and start swimming. We stop at either the pre-planned turn time, the rock bottom for 70', or the turn pressure for 70', whichever comes first. When we reach 40', we can start swimming back. However, if we reach rock bottom at 40' before we get back to the boat, we need to stop swimming back and rise then and there even if there is no emergency.

All of that figgerin' gets tiresome, which is why some people prefer to work out safe approximations such as the rule of thirds or sixths, modified to take current, springs, siphons, and what-not into account.

Or at least, that's my n00b understanding.

(there's another factor, namely our limits for so-called "no deco"

or "minimum deco" diving, but we are strictly talking gas management here)

Last edited:

All of that figgerin' gets tiresome, which is why some people prefer to work out safe approximations such as the rule of thirds or sixths, modified to take current, springs, siphons, and what-not into account.

It's all about mitigating risk, and maintaining reserves. The method of calculating "rock bottom" (aka minimum gas or bingo gas) is a way of ensuring that each team member always maintains enough gas to get another diver to the next gas source from wherever you are. (Note that "next gas source" for recreational diving is the surface.) It may seem as though the calculations are onerous, but in point of fact, most of us dive only a couple of different kinds of tanks, and once you have figured out what RB for, say, 100 feet and 60 feet are, you just plug the number in and set that gas aside.

THEN you figure out what kind of dive you're doing. If it's a drift dive from a live boat and you can come up anywhere, you can use all the gas other than your safety reserve -- "All available gas" dive. If you would LIKE to get back to your starting point (eg. shore dive) but you don't HAVE to (can surface swim in), you can use half of your available gas. If you MUST return to your starting point, then you have to figure enough gas to get you and a buddy from where you are back to the starting point (eg. anchor line) AND up to the surface, so you divide the usable gas into thirds. (That way, you're keeping twice as much gas in reserve as it took YOU to get where you are, so you can get you and your buddy back.)

Some people simplify that kind of system by simply diving thirds on all recreational dives, which is excessively conservative for some, and probably not conservative enough for others.

As you become more facile with the concepts and the calculations, you also recognize that, if you are doing a multi-level dive, your RB is changing as you move shallower, so your usable GAS is changing, as well. There is no point in reserving the 1500 psi RB (for 100 fsw in an Al80) when you've long since left 100 fsw, and are now cruising the reef at 30. That's why we're "thinking divers".

When you first hear about these ideas, it may seem ridiculously complicated. But in fact, the math is simple, it can be boiled down to some easy rules of thumb, it does NOT unduly truncate dives or maintain ridiculous reserves, and it does make it likely that everybody will come home safe. It also helps identify dives which are simply not practical on the gas supply available, which is probably it's highest and best use.

(Note that "next gas source" for recreational diving is the surface.)

I found all the posts about the definitions of terms interesting. Scuba, like many other specialty areas of interest, has developed (and is still developing) its own argot (specialized language). This means it often uses words differently from the way they are used by the general public. For that reason, going to a dictionary for the definitions of these terms can lead to more confusion than help.

When PADI created the "Recreational Dive Planner," for example, it was not creating a table for nonprofessionals to use, implying that the professionals are to use a different dive planner. It was categorizing a certain combination of depths and bottom times as "recreational" dives to distinguish them from dives that exceed those depths and times and require decompression procedures not included in the table planning. (I know I greatly oversimplified that explanation.)

Unfortunately, although the SCUBA community has brought terms like "recreational" and "technical" into its argot, it has not clearly and consistently defined them. I quoted TSandM's statement above because it is consistent with the definition I got from my technical instructor. For our purposes, we have agreed on this differentiation: a recreational dive is one in which a direct ascent to the surface in case of an emergency is a viable alternative. In technical diving, the diver has a "ceiling" which prevents that ascent. It could be a hard ceiling (cave roof or boat deck), a soft ceiling (required decompression stop), or both.

Well put, Reg. And the figuring can also be approximated with a rule of thumb based on depth, as TSandM suggests . . .Some people use gas management strategies [snip] that take this into account. [snip] All of that figgerin' gets tiresome, which is why some people prefer to work out safe approximations such as the rule of thirds or sixths [snip]. Or at least, that's my n00b understanding.

[snip] once you have figured out the RBs for, say, 100 feet and 60 feet, you just plug the numbers in and set that gas aside. As you become more facile with the concepts and the calculations, you also recognize that, if you are doing a multi-level dive, your RB is changing as you move shallower, so your usable GAS is changing, as well. There is no point in reserving 1500 psi RB (for 100 fsw in an Al80) when you've long since left 100 fsw, and are now cruising the reef at 30. That's why we're "thinking divers." When you first hear about these ideas, it may seem ridiculously complicated. But in fact, the math is simple, it can be boiled down to some easy rules of thumb, it does NOT unduly truncate dives or maintain ridiculous reserves, and it does make it likely that everybody will come home safe.

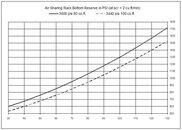

As an example, you can work out consumption on a shared-gas scenario at various depths, including time to get sharing and get linked up, time to ascend, and time to do your stops. Among your assumptions will be combined consumption rate of the two divers and their ascent rate, perhaps also complications such as currents and overheads. The result is a shallow curve plotting consumption against starting (fubar) depth. This example is for a pair of non-deco single-tank divers sharing air with a combined RMV of two cubic feet per minute:

Now it's possible to choose an appropriate scalar multiplier as a rule of thumb. For example, you could decide that your rock bottom reserve when diving a single low-pressure 80 will always be 15. Then for example at 100 feet we must get shallower once one of us is at 1500 psi. Once we reach, say, 80 feet our new rock bottom reserve is 80*15 or 1200 psi.

Of course, prudence dictates I stress that the assumptions you make, the multiplier you choose, and the dives and conditions you undertake still require you never turn off that first and best dive planner alluded to by TSandM: your brain.

Happy new year all,

Best practices always,

Bryan

On of THE best posts I read on this subject on SB. It clearly shows the reasoning and viewpoints on HOW to get to a dive (gas) plan.It's all about mitigating risk, and maintaining reserves. The method of calculating "rock bottom" (aka minimum gas or bingo gas) is a way of ensuring that each team member always maintains enough gas to get another diver to the next gas source from wherever you are. (Note that "next gas source" for recreational diving is the surface.) It may seem as though the calculations are onerous, but in point of fact, most of us dive only a couple of different kinds of tanks, and once you have figured out what RB for, say, 100 feet and 60 feet are, you just plug the number in and set that gas aside.

THEN you figure out what kind of dive you're doing. If it's a drift dive from a live boat and you can come up anywhere, you can use all the gas other than your safety reserve -- "All available gas" dive. If you would LIKE to get back to your starting point (eg. shore dive) but you don't HAVE to (can surface swim in), you can use half of your available gas. If you MUST return to your starting point, then you have to figure enough gas to get you and a buddy from where you are back to the starting point (eg. anchor line) AND up to the surface, so you divide the usable gas into thirds. (That way, you're keeping twice as much gas in reserve as it took YOU to get where you are, so you can get you and your buddy back.)

Some people simplify that kind of system by simply diving thirds on all recreational dives, which is excessively conservative for some, and probably not conservative enough for others.

As you become more facile with the concepts and the calculations, you also recognize that, if you are doing a multi-level dive, your RB is changing as you move shallower, so your usable GAS is changing, as well. There is no point in reserving the 1500 psi RB (for 100 fsw in an Al80) when you've long since left 100 fsw, and are now cruising the reef at 30. That's why we're "thinking divers".

When you first hear about these ideas, it may seem ridiculously complicated. But in fact, the math is simple, it can be boiled down to some easy rules of thumb, it does NOT unduly truncate dives or maintain ridiculous reserves, and it does make it likely that everybody will come home safe. It also helps identify dives which are simply not practical on the gas supply available, which is probably it's highest and best use.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 139

- Views

- 10,482

- Replies

- 13

- Views

- 2,058

- Replies

- 17

- Views

- 1,742